Changes in workers action

We have recorded labor movements in different regions and industries through statistics of labor movement data over the past ten years. It presents a social, political and economic situation beyond the official narrative, and also foreshadows future changes in the labor movement.

First, China's economic composition and development model have undergone significant changes - from relying on low-cost export-oriented manufacturing for more than three decades to the rise of service industries such as online shopping and food delivery based on Internet platforms. As a result, more and more labor disputes have emerged in service industries ranging from health care and catering to banking and finance, as well as related transportation industries such as freight drivers.

On January 25, 2021, hundreds of nursing staff at Yan'an University Affiliated Hospital in Shaanxi Province launched a sit-in demonstration, demanding that the hospital increase wages and pay pension and medical insurance for employees. That month, couriers at Best Company in Hebei Province went on strike because their bosses had not paid wages, resulting in tens of thousands of undelivered packages piling up outside the warehouse without anyone delivering them.

It can be seen that while labor disputes in traditional manufacturing industries are still mired in quagmire, labor conflicts in emerging industries are also expanding in the form of new wine in an old bottle.

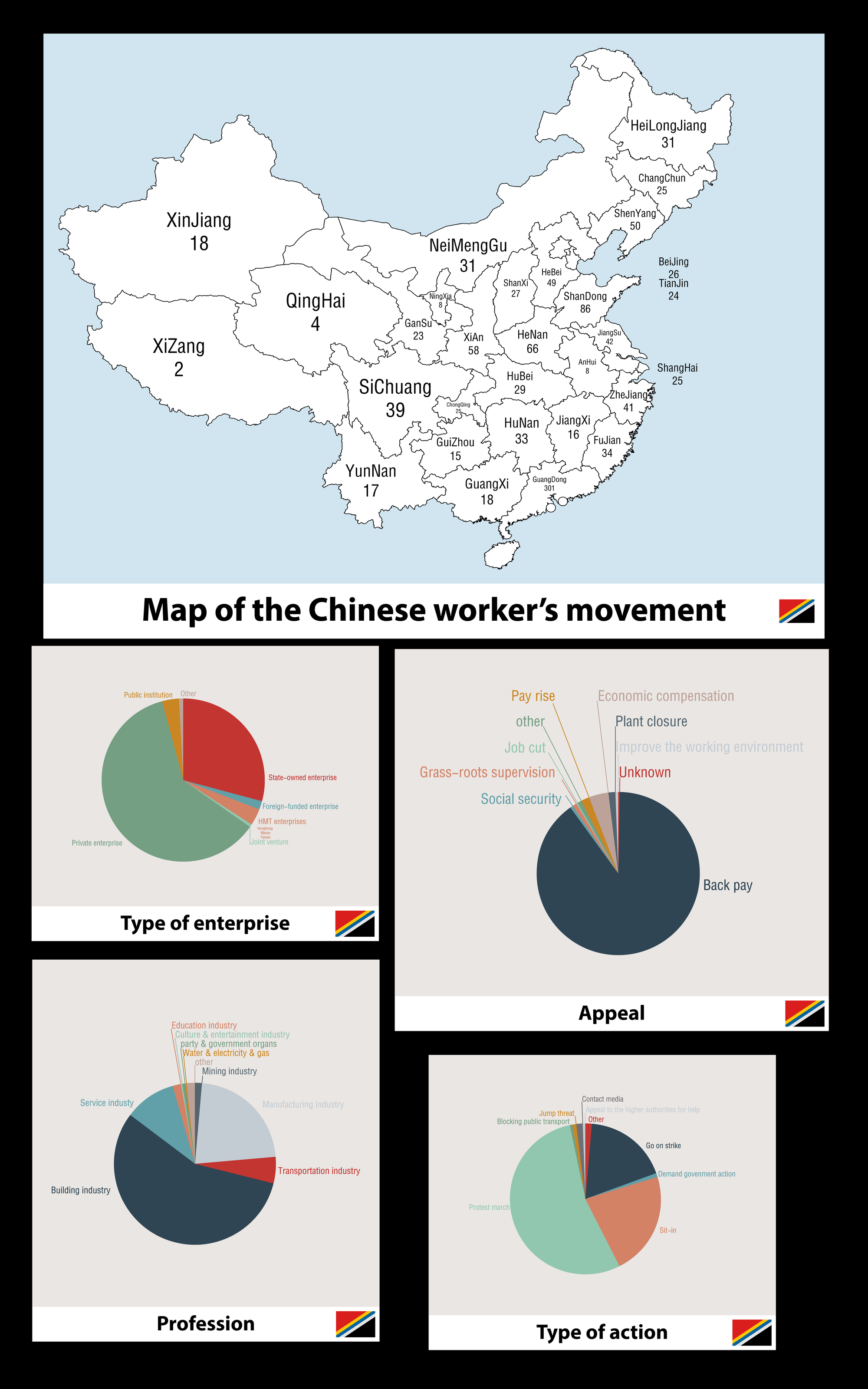

Second, since the 1990s, urbanization and economic development in China's inland areas such as Sichuan and Henan have accelerated, providing a large number of labor forces for the more developed coastal areas. As companies expand to inland areas, labor disputes in these areas also surge.

Once upon a time, Shenzhen was the epicenter of worker protests in China, but that has changed. In 2015, 75 manufacturing worker protests were recorded in Shenzhen, accounting for 75% of the total collective actions of workers in the city that year. But just two years later, in 2017, this number dropped to 22, accounting for half of the collective actions of workers in the city that year.

Finally, traditional social structures related to labor are eroded, and people are increasingly isolated and fragmented in society. Plus the first generation of migrant workers is gradually getting older, and the instability of labor is increasing day by day. Social welfare systems such as pensions are facing unprecedented challenges. Since 2000, factories have replaced the “kinship and regional connections” that workers once relied on, providing workers with a natural place for mutual solidarity and connection.

Once they arrive in Shenzhen and other places, these workers from Sichuan, Henan or other inland areas will find that differences such as region and ethnicity are no longer important, because in the face of long working hours, low wages, and poor treatment, labor disputes have become their common concern.

The ultimate question faced.

This has become increasingly evident over the past decade. With the rise of social media such as Weibo, WeChat, Douyin, and Kuaishou, social media has built a new level of relationships, which is more prevalent than traditional face-to-face connections between people. Social media has reshaped the dynamics of labor protests in China, as demonstrated by the 2018 protests at Shenzhen Jasic Technology Co., Ltd. During that protest, protesters "effectively used digital media to express the solidarity of workers and students," despite Chinese authorities removing and blocking content.

However, truly effective collective action requires concerted action both offline and online. Convenient and fast communication online can also make people ignore the actual face-to-face actions offline. Eventually, social media may in turn become a tool used by employers and authorities to monitor and suppress workers. Looking back at the data over the past ten years, we will find that manufacturing protests have declined significantly as a proportion of China’s total labor protests. In 2013, factory worker protests accounted for 46.5% of the total; by 2020, this number only accounted for 11% of the total.

In the decade between 2011 and 2020, the service and transportation industries gradually replaced manufacturing and dominated protests. This has been one of the most obvious trends in worker protests. The main body of Chinese workers' protests have always been construction workers, and their proportion of the total number of collective actions has remained stable at around 40%. At the beginning of 2020, this proportion increased significantly as a large number of construction companies encountered severe impacts on cash flow and economic uncertainty, with almost every case involving unpaid wages.

Labor disputes in the service industry intensify

Data shows that at the start of the 2010s, worker protests occurred more often among people in big cities with less specialized jobs, such as sanitation workers, cleaners, and shop and restaurant employees. But by the mid-2010s, protests were spreading across the country in a variety of industries, including hotels, bars and karaoke rooms, gyms, technology companies, banks and financial companies, medical institutions, kindergartens and other private educational institutions. There have been employee protests at cram schools and driving schools; even at golf courses and amusement parks, professional football teams, television stations and local media outlets.

In June 2014, high school teachers at Chenzhong Middle School in Chongqing went on strike to protest, demanding that the school pay back wages and safeguard their “fair and equal treatment.” In the same month, employees of China Mobile demonstrated at Shandong Heze Mobile Company and the municipal government to protest against unfair layoffs. In December of the same year, employees of China Resources Vanguard Supermarket in Tangshan, Hebei Province held a protest outside the store, demanding that the company give them the same layoff compensation as employees of another branch. The workers' banner read: "China Resources Vanguard, give me equal treatment!"

Before 2017, protests in the transportation industry tended to be dominated by taxi drivers, with few couriers or food delivery people protesting. But in the past few years, things have changed dramatically. The rapid development of e-commerce has promoted the large-scale development of the gig economy in food delivery and other express delivery service industries, and the number of employment in this emerging industry has increased dramatically.

However, because its labor relations are more uncertain than in traditional industries, labor disputes have also spread with the expansion of the industry. In the late 2010s, e-commerce developed significantly in China. In 2019, China's e-commerce sales totaled US$1.9 trillion, more than three times that of the United States, the world's second largest e-commerce market. In 2020, China accounted for nearly 55% of the global e-commerce market share. More and more people are starting to shop online, and logistics companies' demand for drivers is growing steadily, even during the global spread of the coronavirus in 2020. In addition, the government has encouraged the construction of community express delivery stations and increased so-called flexible employment.

A temporary "gig economy" to address social concerns about rising unemployment

In the first half of 2020 alone, Meituan, China's largest online food delivery platform, added 1.4 million employees. A survey of these gig workers found that 30% joined the platform after losing their jobs in other industries, and a significant number of them had at least a bachelor's degree, accounting for nearly 25% of Meituan's 2.95 million gig workers.

Since 2015, the number of taxi driver protests has declined. However, the COVID-19 epidemic in 2020 caused taxi revenue to plummet, but the company collected a lot of fees, leading to a significant surge in driver protests. 2020, middle 116 taxi driver protests were recorded, double the 54 recorded in 2019. This trend is even more pronounced when we look at taxi drivers within the context of labor protests as a whole. In 2013, taxi driver protests accounted for about 15% of the total, which dropped to 8.2% in 2016 and only 3.9% in 2019, but by 2020, this number rose back to 14.5%. Since 2017, strikes and protests by Chinese app platform transport workers have become mainstream. In the face of fierce industry competition, platforms continue to cut costs to seize market advantages. Unstable income and harsh fine systems have led to frequent worker protests occurring frequently.

From January 2017 to December 2020, 220 collective protests initiated by takeaways and couriers were recorded, accounting for approximately one-third of all transport industry protests during that period. Food delivery drivers on app platforms such as Meituan and Ele.me have long faced ubiquitous labor rights traps, including 18-hour shifts and penalties for late deliveries. Under the control of the algorithm, workers have no bargaining power, and even after a work-related injury occurs, the platform does not recognize the labor relationship at all, making workers miserable on the road to safeguarding their rights.

In the next ten years, China's economic structure will continue to undergo further changes, especially the shift of the focus of the industrial structure to the service industry and e-commerce. More labor disputes may focus on new types of flexible employment positions. This will bring a series of new challenges to China's labor relations and labor rights.

Regional changes in the labor movement

In the early 2010s, most of China's labor disputes were concentrated in the southeastern coastal provinces, especially the economic powerhouse Guangdong. However, as low-cost export-oriented industries gradually shift abroad and urbanization develops inland, the overall proportion of worker protests in Guangdong continues to decline.

The changing nature of workers’ organizing and resistance

After 2015, the service industry gradually replaced manufacturing as the industry that contributes the most to China's GDP. This was followed by an increase in the instability and discreteness of the labor force, which led to significant changes in the way workers organized and acted collectively.

In the past, manufacturing, mining and other industrial sectors often employed large numbers of workers in fixed locations; one of the most obvious trends now is a marked reduction in the number of large-scale protests.

The most recent large-scale factory worker protest was the strike at Dongguan Yue Yuen Shoe Factory in April 2014. At that time, 40,000 workers went on strike for two weeks to protest against low wages and the company's unpaid social security contributions. Since 2015, many large factories have closed or laid off most of their workers. The remaining factories are mostly more stable and more profitable because they can provide relatively reasonable wages and have fewer problems with worker protests.

The decline in the number of protest events involving a thousand or more workers in the data may be partly due to the fact that in the first few years of the 2010s, large-scale strikes and demonstrations were easier to find on social media than smaller protests. However, the more important reason is that in the second half of the 2010s, the government became more forceful in curbing any collective actions that threatened social stability and damaged the image of the Communist Party.

The most prominent setback for the government on labor issues occurred on March 11, 2016, in Shuangyashan City, Heilongjiang Province. At that time, the governor of Heilongjiang Province, Lu Hao, was attending the National People's Congress in Beijing, and thousands of angry coal miners marched on the streets of Shuangyashan to petition, demanding that Heilongjiang Longmei Group pay wages that had been overdue for more than two months. Longmei Group is a state-owned enterprise that was heavily in debt due to overcapacity in coal production. What made the workers even more angry was that provincial governor Lu Hao publicly stated at the two sessions that Longmei Group "does not owe underground workers a penny." Longmei workers protested angrily. This protest was the largest protest against a state-owned enterprise in many years. This move forced the local government to ask Longmei Group to pay all workers' wages.

But authorities have also made it clear that this type of protest will not be tolerated. On March 13, the police stormed into workers' residences, arrested many miners participating in the demonstration, and released photos of at least 75 wanted persons. The logic of the central government's zero-tolerance strategy is to maintain the government's stance of harshly punishing "troublemakers" so as to intimidate other potential labor leaders and prevent other regions from imitating collective protests.

After the Shuangyashan incident, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council introduced new public security measures, and all responsibilities for large-scale mass incidents fell to local governments. In other words, the government has zero tolerance for mass incidents, and top local officials may be removed from office if these incidents occur. In the late 2010s, labor non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Guangdong Province also continued to be suppressed. Over the past decade, these NGOs have ample experience in providing local factory workers with the specific skills they need for collective action. In several well-known cases of workers' rights protection, these NGOs successfully brought employers to the bargaining table, creating a new model of collective bargaining in practice and highlighting the absence of official trade unions in defending workers' rights.

The government's suppression of traditional labor NGOs has left workers without the guidance and reliable support of professional protest knowledge. Therefore, more and more workers are turning to online organizing and using various communication software to fight. For example, in 2016, Walmart employees staged several strikes to protest against the company’s changes to its working hour system. The actual number of people participating in the protests in person is limited, but it is estimated that about 100,000 Walmart employees have entered the newly established online support group, which helps to alleviate the loneliness of protesting employees when dealing with powerful employers.

With online organizing, everyone, even colleagues thousands of miles away, seems to share a common identity, face the same difficulties, and find common solutions. Later, in the summer of 2018, crane operators and truck drivers adopted similar tactics, organizing nationwide protests against falling wages and deteriorating working conditions. That same year, workers at Shenzhen Jasic Technology Co., Ltd. took a step further to use social media to connect with student groups and supporters. However, there are risks associated with online organizing, and Jasic workers and their supporters have been arrested and detained in large numbers.

The subsequent arrests of ‘delivery boy’ leader Chen Guojiang in 2019 and February 2021 also proved this. Chen Guojiang is also known as the leader of the Riders Alliance. He once established a huge mutual aid network for delivery riders, the "Delivery Knights Alliance", connecting more than 14,000 riders. Chen Guojiang has released many videos calling on everyone to pay attention to the rights of riders. He exposed the platform’s suppression of workers and criticized the platform.

Blatantly violating labor laws, fining workers for late delivery of takeaways and other inappropriate behaviors.

In September 2020, Chen Guojiang once said that he hoped that the authorities could set up a trade union-like organization specifically for food delivery riders. He hoped that this organization could represent workers and platforms to negotiate worker treatment issues, and that the local government would take the lead in regulating labor standards in the food delivery industry.

Rather than allowing private companies such as Meituan and Ele.me to exploit food delivery riders at will. He was eventually arrested by officials in 2021. His arrest is certainly a warning for collective action online. The official message could not be clearer. No matter how inactive, closed-minded, or out of touch with the demands of workers, the official trade union organization cannot tolerate influential opinion leaders outside the official organization speaking out for the workers.

In fact, most current worker protests are poorly organized. Struggles tend to be small (fewer than a hundred participants) and short-lived, and focused on resolving the specific dispute at hand. Protests usually seek to draw social attention to the plight of workers and for government intervention, rather than direct dialogue and collective consultation with employers or local governments. Many workers are no longer even holding physical protests, but are simply posting calls for help online, actions that often do little to resolve the incident.

Government Facing Labor Conflict

Perhaps to avoid a repeat of the Shuangyashan incident, the central government went to great lengths in the late 2010s to ensure that laid-off workers, especially coal miners and steelworkers, were fully paid, and also provided workers with financial aid during the subsequent shutdown or curtailment of large state-owned enterprises with adequate compensation. Since 2019, as economic uncertainty continues to intensify, the Communist Party of China has continued to emphasize the "six stability" and prioritized "maintaining stable employment". President Xi Jinping has repeatedly emphasized the importance of "six stability" and emphasized that "employment issues should be given top priority." Chen Qiqing, a professor at the Central Party School, interpreted the "Six Stabilities" in an interview with the "Study Times" in May 2020, and made it clear that "if employment cannot be maintained, everything may be lost, even the bottom line of social stability."

- Pro IWA China Group